Monday mornings are always quite stressful wherever you work, and in Kule refugee camp in Ethiopia, this was no exception.

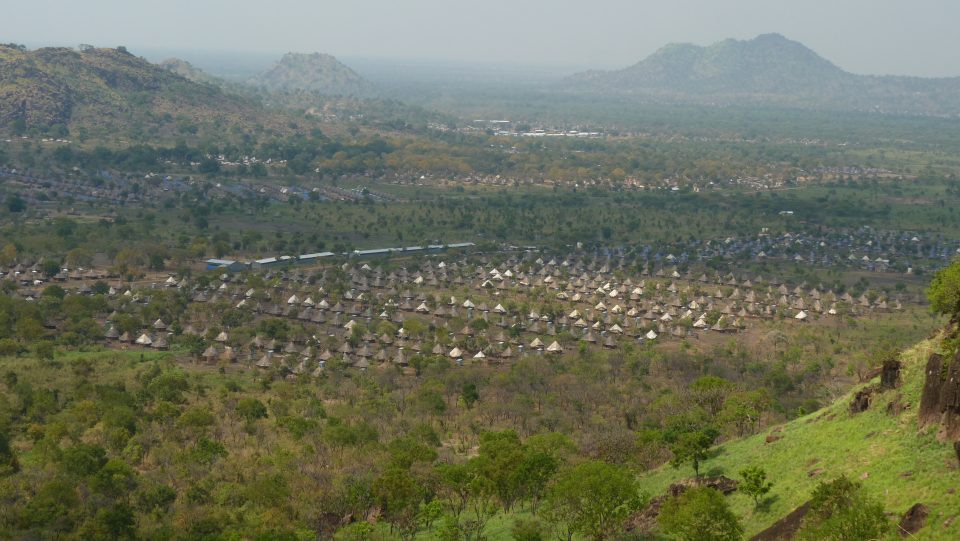

Kule refugee camp has a population of over 55,000 South Sudanese people displaced from their homes due to the ongoing fighting. It was here that I was working as the Maternity Services Manager for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

The week began with me listening out for the buses that rumbled through the camp from the town an hour away. My ten staff members would be on board, though sometimes there were absences. This being an area with endemic malaria, many staff succumbed to bouts of malaria so I was often faced with a shortage of staff.

Once the team assembled, I assigned different duties for the day. The camp has six outlying health posts, and each must be staffed by a midwife. A camp of this size sprawls over a large area and the only way to get around is by foot, so the access to care provided by these health posts is very important. The health posts dealt with immunisations, first aid, antenatal care, health promotion, and acted as a referral centre for more complicated cases.

On this Monday morning after staffing the health posts I was left with only the supervisor, a junior midwife and myself to work in the maternity department which comprised of 10 postnatal beds and two labour rooms. There should have been at least four midwives not including myself, but this was not an unusual situation.

The maternity department was part of the larger Health Centre – a basic facility with seven departments but no operating theatre or blood bank.

After a quick handover with the staff who had worked the night shift, we set to work. We discharged the delivered patients, looked after the tiny babies who were being tube fed, completed the morning drug round and worked out the priorities among those who were labouring. We had an early labour room where the women waited quietly – resting and being cared for by female companions.

That morning the babies were born without complications and everything was going smoothly, until we heard a commotion and shouting.

The midwife and I followed the noise to the road outside the health centre, donning gloves and cloths to help a woman who, it transpired, had delivered on the road outside the gate. This was a frequent occurrence – we called them “on the road babies”. This woman’s companion had spread her toub – a long piece of cloth – over both like a tent and they were kneeling underneath it. It was very discreet and the baby was fine – if a little sandy.

The women often had a long walk to the Health Centre and were desperate to come for care because we provided a ‘dignity kit’ for those who delivered with us. This kit consisted of a bucket with a lid, clothes for the baby, a comb, reusable sanitary pads, underpants and a little mirror.

Soon after we had another emergency admission of a woman in early pregnancy who was bleeding and in pain. After assessment the midwife quickly performed a manual vacuum aspiration and the woman was almost immediately relieved of pain, bleeding and anxiety.

It had been a busy few hours and now we only had one woman still in the early labour room. She had been quiet and uncomplaining while we dealt with the most demanding cases first, but when we checked her we realised that she was in a huge amount of pain that she had borne without a murmur and her uterus was tense and wooden to the touch.

This was a concealed abruption – an obstetric emergency. We quickly transferred her to the referral centre an hour away with an accompanying midwife. I wish that I could tell you that there was a happy end to this story, but sadly there wasn’t. We found out the next day that by the time she was operated on it was too late for her and the baby.

Life for refugees is hard and I saw much silent suffering especially among the women and children. Hopefully the work that MSF does here in this camp – welcoming the women, showing them respect and treating them with kindness and compassion – goes some way to create a positive experience for them and gives the babies a better start in life.

Things quietened down for the afternoon in the Health Centre, probably due to the heat in the tin roofed building. For me the afternoon meant paperwork in a hot tented office with intermittent internet.

This was a fairly ‘normal’ Monday working for MSF – it’s stressful but always rewarding and there’s always something to learn.

To find out more about the work of MSF and details of how you could get involved please visit msf.org.uk/midwife

Jonquil Nicholl

MSF Maternity Services Manager